From Fear to Fascination, Teaching Children about Pollinators

- Melissa Reve

- 20 hours ago

- 3 min read

When children are very young, their relationship with the natural world is often open and unfiltered.

They notice.

They lean in.

They ask questions that don’t yet carry judgement.

Somewhere along the way, many children learn that certain parts of nature are something to fear — especially insects. They learn what is “gross,” what should be avoided, what should be sprayed, trapped, or removed.

Very few children arrive at these ideas on their own.

Fear is learned.

And once fear takes root, curiosity quietly slips away.

In early childhood and primary education, science learning is framed around observing living things, understanding what plants and animals need to survive, caring for the environment, and developing inquiry skills through questioning and exploration.

In practice, educators are navigating additional layers — safety considerations, limited time, parental concerns, and classrooms where many children already feel uneasy around insects.

While the curriculum invites curiosity, the everyday reality can limit opportunities for children to experience insects as living, purposeful parts of the natural world. As a result, many classrooms rely on posters, simplified diagrams, or a narrow focus on “safe” animals.

Pollinators are a perfect example.

We talk about bees — and bees matter — but many children never learn that pollination is carried out by a wide range of creatures, in many different ways. Flies, beetles, butterflies, moths, wasps, and even tiny midges all play roles that are just as essential.

Some visit flowers on purpose.

Others help by accident.

Some work during the day.

Others quietly at night.

The variety of pollinators is where the real learning happens.

One of the most powerful ways to reopen curiosity is through beauty.

Not cartoon versions of insects, but real images — close-up, detailed, and respectful. When children are invited to look closely, something shifts. Instead of reacting, they begin to notice patterns: hair on legs, pollen stuck to bodies, the shapes of wings, the way different insects move and feed.

The question changes from “Is it scary?” to “What is it doing?”

That is the moment when learning begins.

Curiosity helps children stay open instead of pulling away when something feels unfamiliar. When children remain curious, they engage more deeply, ask better questions, and build understanding rather than avoidance.

This is where science learning and emotional development quietly meet.

There’s also a quieter layer to this conversation that many adults are increasingly aware of.

As fear of insects grows, so does our reliance on chemical solutions in homes and shared spaces. Children absorb these messages early: discomfort should be eliminated, nature should be controlled, small creatures are problems to be solved.

When children learn to understand insects as part of a living system, fear often softens. And when fear softens, behaviour tends to shift without needing to be forced.

As children understand more, their care deepens — and better choices tend to follow.

Pollinators offer children something rare and valuable: a chance to see how small, often unnoticed actions can support entire ecosystems. They show that not all helpers look the same, that contribution doesn’t always look intentional, and that the world depends on quiet cooperation as much as obvious effort.

These are scientific ideas.

They are also deeply human ones.

By presenting pollinators through real images, gentle inquiry questions, and accurate, accessible language, educators can meet curriculum goals while also protecting something precious: a child’s natural sense of wonder.

Sometimes, learning doesn’t need more information.

It needs space to notice.

And sometimes, helping children stay curious is the most meaningful outcome of all.

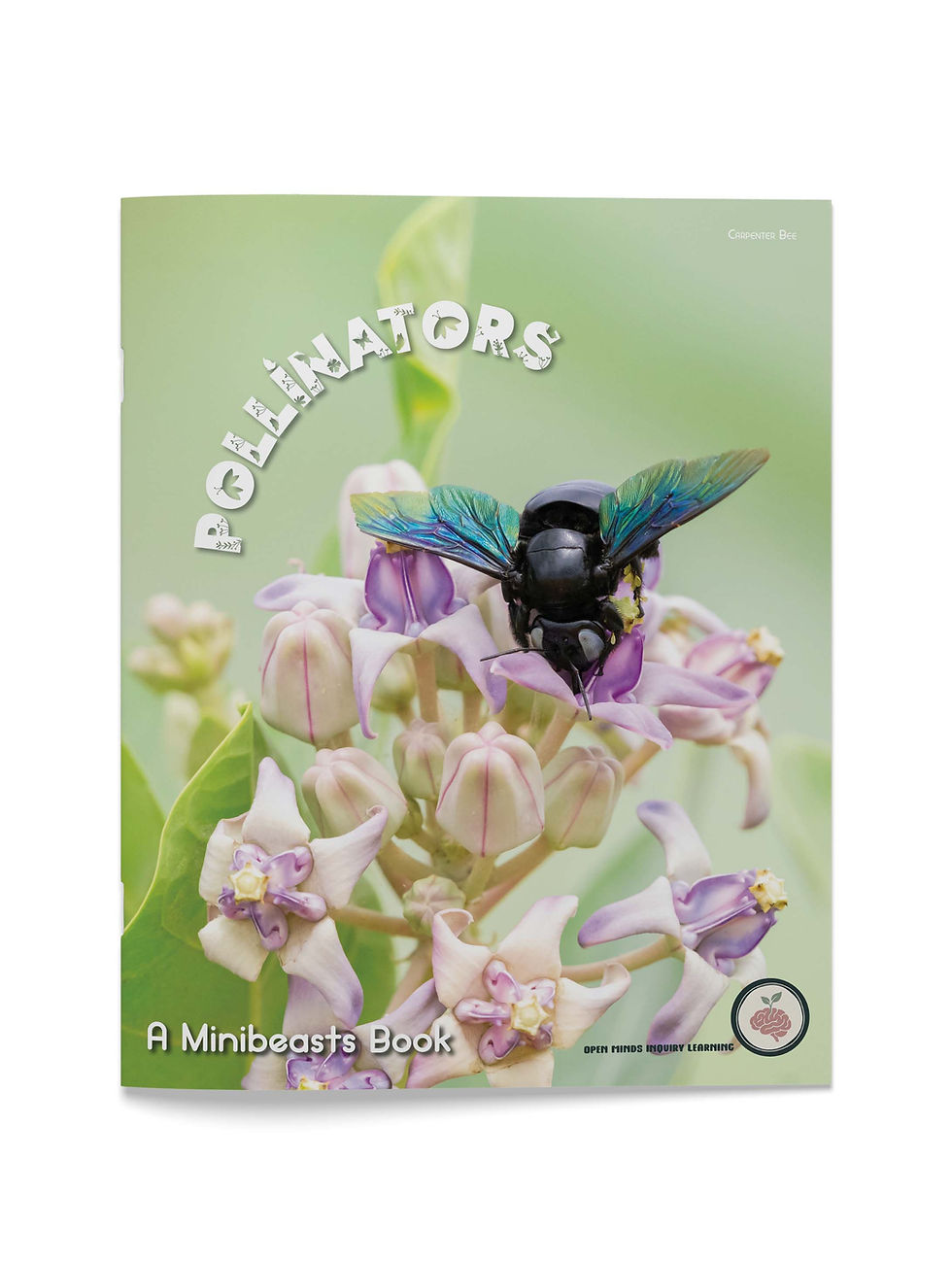

Pollinators - a book made for the classroom

Early years and primary science curricula ask children to observe living things, explore how plants and animals survive, and begin to understand how environments work as connected systems.

In reality, educators are often balancing:

safety concerns around insects

limited time for hands-on science

parental anxiety

and children who have already learned to react with fear rather than curiosity

This can make it difficult to explore insects in meaningful ways, even when the curriculum encourages it.

One way to bridge this gap is through shared reading and close observation.

Using real photographs, simple scientific language, and open-ended questions allows children to:

notice without needing to touch

compare insects safely and thoughtfully

learn that pollination happens in many different ways

and see insects as helpers rather than hazards

The pollinator book was created with this reality in mind. It supports curriculum outcomes while giving educators a gentle, flexible way to explore insects through inquiry, discussion, and careful looking — without needing live specimens or additional materials.

If you’re looking for a resource for teaching children about pollinators through beauty, accuracy, and curiosity-led learning, you can explore the book here:

Comments